NEWS: Advocacy through storytelling

Friday, August 28, 2015

HDAC Youth members Tj Keeya Talamoni-Marcks and Rodrigo Lupercio are the winners of a nation-wide essay contest and will head to the sixth annual Native Youth Health Summit held in Washington D.C. by the National Indian Health Board in September. Berenice Quirino — Lake County Publishing read full article here.

Summit Recap & Digital Stories

(UPDATED 10/12/15)

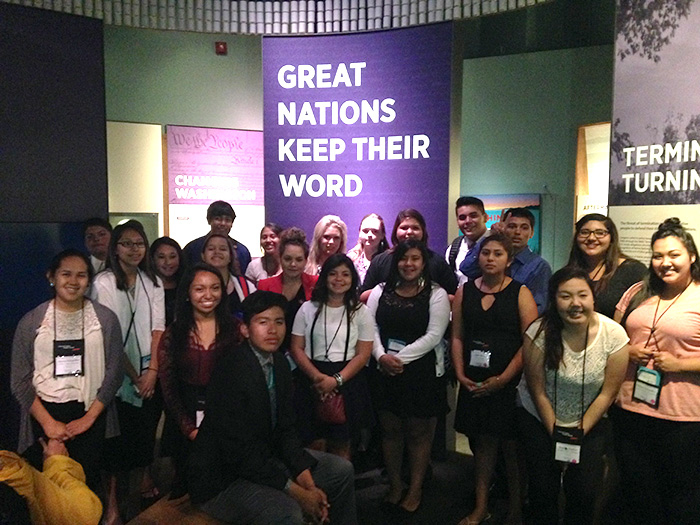

American Indian and Alaska Native youth from across the country came together in Washington, DC for the National Indian Health Board 6th Annual Native Youth Health Summit, “Youth Advocacy: Telling Your Story to Create Change”. NIHB hosted 24 youth from 11 different states and 14 different Tribal Nations and Alaska Native Villages.

The youth told personal stories about the health and resiliency of themselves, their families, and their communities... read full article here.

KQED News: Native American Teenagers Promote Sports to Tackle Substance Abuse

OCTOBER 14, 2015 SHARE

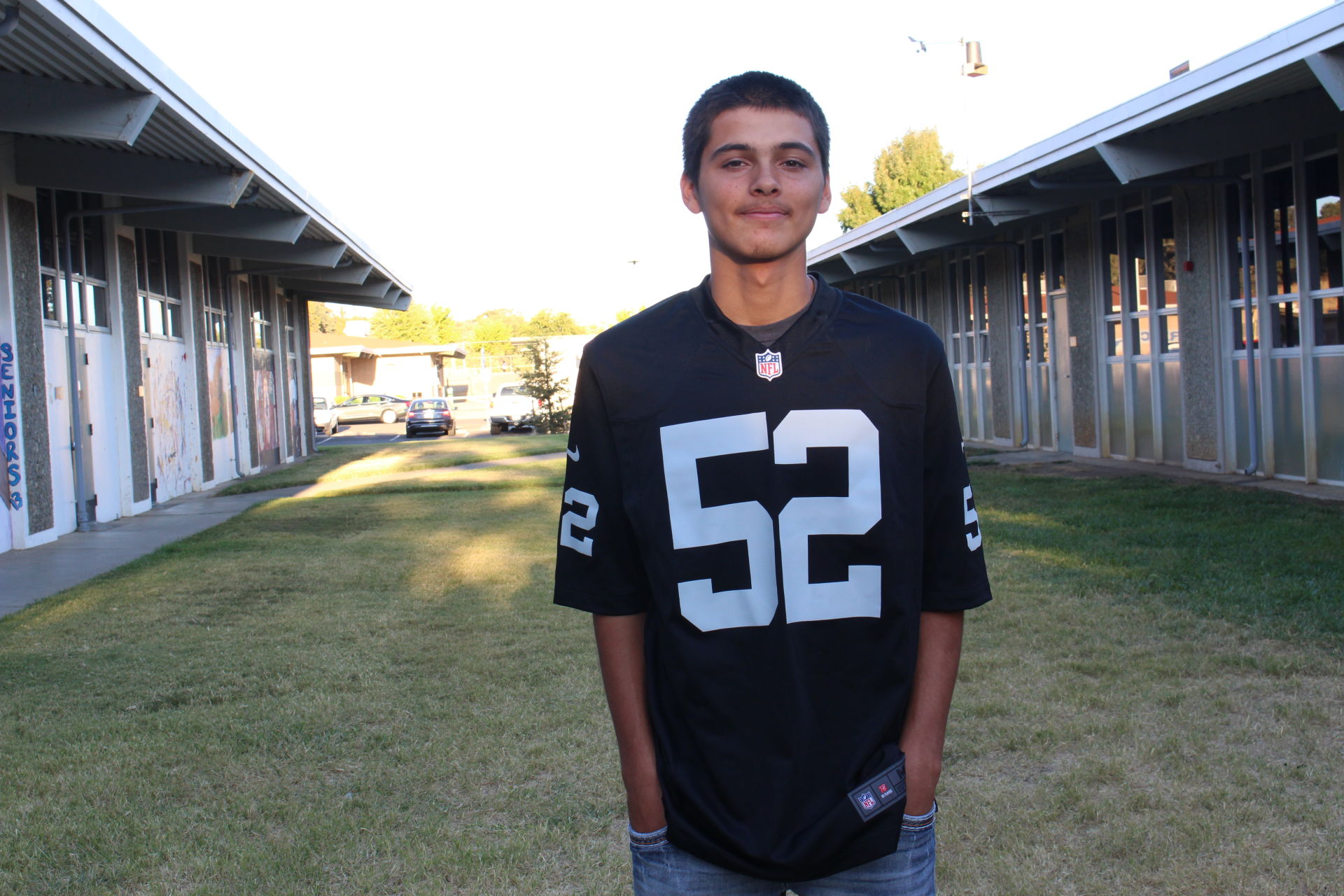

Tj Talamoni-Marcks plays tackle and guard for Clear Lake High. The 15-year-old recently met with staff members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs in Washington, D.C., as part of a native youth summit on health. (Farida Jhabvala Romero/KQED)

Tj Keeya Talamoni-Marcks walks off the field with sweat dripping from his forehead, as more than 20 other Clear Lake High School students finish their grueling football practice in temperatures that reached over 90 degrees.

Clear Lake’s Cardinals are getting ready to play against Colusa High in a few days, and Talamoni-Marcks, a tackle and guard, holds his helmet with one hand and makes a beeline for the water fountain while limping. He recently recovered from a toe injury, and complains about pain in his foot. Still, he shrugs it off, saying pain and visible bruises on his arms are “part of the game.”

Sports are a source of pride for Talamoni-Marks and his family, of Pomo Indian and Samoan descent. The 15-year-old wants to follow in his parents’ footsteps — his mom was a basketball star and his dad “running back of the year” at Clear Lake High, the only high school in Lakeport, about 120 miles north of San Francisco.

“Sports keep me away from drugs and alcohol. They keep me healthy,” he says. “I want to get other Natives healthier too, and I think sports could be the way.”

His teammate and childhood friend, Rodrigo Lupercio, agrees heartily.

For both teenagers, sports have become an inspiration to tackle a bigger challenge than any football match: substance abuse among Pomo Indian communities in Lake County.

Nationwide, Native Americans are more likely to die of alcohol-related causes such as chronic liver disease and fatal motor crashes involving alcohol than any other ethnic group in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control. Native Americans also have very high rates ofcigarette smoking compared to whites, blacks, Hispanics or Asians.

Lupercio, from the Big Valley Band of Pomo Indians, has witnessed the toll of alcohol and tobacco use on his grandfather. The two are very close. They used to play baseball and “always have a good time” together, he says. But now, Lupercio, just 14, fears the worst.

“He shakes a lot and has a hard time walking. Because he drank so much throughout all of his life, it became part of his system. He needs it,” said Lupercio. “It makes me sad because I know I won’t be seeing him in a couple of years.”

Rodrigo Lupercio plays football, basketball and baseball at Clear Lake High. He says more physical activity through sports at Indian reservations could decrease substance abuse. (Farida Jhabvala Romero/KQED)

Talamoni-Marcks tries to convince his mother to quit smoking after seeing another smoker, his former karate teacher, have to breathe through a hole in his throat. The lesson?

“I don’t think I would ever,” he says of smoking. “I hate it. (My mother) is addicted to it, and I hate to see her like that.”

Last summer, the two teenagers took their views on addiction a step further. As part of their applications to a native youth health summit in Washington, D.C., they wrote essays on ways to improve the health of their communities.

The National Indian Health Board, a non-profit representing tribal governments organizing the summit, selected them along with 28 others to meet with staff members for the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs and discuss their ideas.

Lupercio spoke of seeking greater participation in sports at the Big Valley Rancheria, the reservation where he’s spent most of his life.

“Down in the reservation, I’d say all Indians should have their own sports teams. I think that would get them active, and they wouldn’t want to do drugs. They’d just want to just do sports,” he said.

Talamoni-Marcks wants to keep sporting events with Native participants alcohol and smoke-free.

“Give them water rather than beer, don’t let them smoke there. And just have a fun game, while keeping healthy,” said Talamoni-Marcks.

The teenagers also want a rehab and wellness center for youth and adults within their tribal communities, and greater educational opportunities that will lead to better jobs. The unemployment rate for Native Americans was almost double the national rate in 2013, according to figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Talamoni-Marcks and Lupercio hope their meeting in Washington with the Senate staffers will eventually bring much needed resources to change the health outcomes in their communities. They believe that advocacy can make a difference. But if that takes too long, they dream of another path that does not involve the federal budget.

“I want to play professional sports to help my family, to help my community, to come back and donate money while doing stuff I love to do,” said Talamoni-Marcks.

For Lupercio, who wants to become a professional football player, the most important thing now is emotional support for his grandfather.

“I just want to say, ‘I love you grandpa, and you’ll always be in my heart,’ ” he said.